There are two streets named Vanderbilt in Brooklyn, Vanderbilt Ave. in Clinton Hill and Prospect Heights and Vanderbilt St. in Windsor Terrace. That one is named for 19th-century politician and jurist John Vanderbilt, a member of a family that arrived from Holland in the 1650s, with the family named meaning “near the town of Bilt” in Utrecht, another Netherlands place name that also wound up in Kings County.

Vanderbilt Ave. is named for “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, who initiated the first ferry service from Staten Island to Manhattan and later controlled multiple steamship lines and railroads. The Vanderbilt family owns a large plot in Moravian Cemetery in Staten Island; William K. Vanderbilt constructed Long Island’s first auto throughway; and he’s the great-great-great grandfather of TV newsman Anderson Cooper. The Clinton Hill Landmarks Designation report names John Vanderbilt as the avenue’s namesake, but I take issue with it because it’s paralleled by Clermont Ave., the name of Robert Fulton’s famed steamship, and Clinton Ave.: the street was likely named for DeWitt Clinton’s involvement in the construction of the Erie Canal, as men who had a hand in NYC’s waterborne growth, and the instruments of that growth, are honored in this region.

Few areas of Brooklyn have changed as much as Atlantic Ave. just east of Flatbush Ave.. Today it’s dominated by the Atlantic Terminal shopping area and Barclays Center. When I went to school in the area, Atlantic Ave. featured meat wholesalers and slaughterhouses. If I walked from school at Washington Ave. back to the subway at Flatbush, I’d sometimes have to dodge meat carcasses dangling on hooks. It was Brooklyn’s own Meatpacking District.

Professional football had its AFL from 1961-1970, when the New York Jets won their only Super Bowl. But Brooklyn had the AFL long before it was known as a football league, with another AFL… American Food Laboratories… at #860 Atlantic Ave. where it faces Clinton Ave.

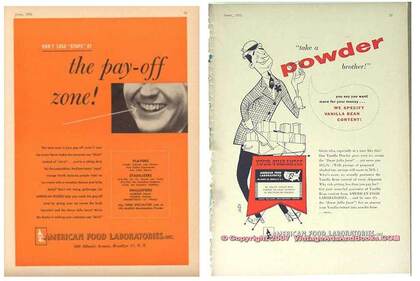

What kind of food was concocted in the American Food Laboratories? Ice cream flavoring. Since this was the 1940s and 1950s when vanilla, chocolate and strawberry were the most-consumed ice cream flavors, that’s what was offered to ice cream makers by the AFL. Above are a couple of magazine ads that would make a Saul Bass or Milton Glaser proud.

I’d never seen this painted sign during the years 1971-1975, when I went to high school nearby. However: during those years the neighborhood was sketchier than now, and at lunch I stayed in the school building. When I later attended college and worked in Brooklyn Heights between 1975 and 1981 I didn’t explore the area that much either. In those years most of my inhalation of NYC’s infrastructural environment came from glimpses I got when bicycling Brooklyn and Queens in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s before moving to Flushing. It was then, in 1998, that the idea for the website forgotten-ny.com, and the two books it inspired, coalesced.

Smokey Vale’s a combination haberdashery, art gallery and barbershop founded by Jamaica native Paul Howlett at #575 Vanderbilt. I consider it an unusual combination but the hybrid barbershop idea has been done before at Freeman’s Sporting Club near the Bowery, which offers Dewar’s whisky with a trim. The Smokey Vale sidewalk sign uses the Highway Gothic font used on road signs, though not in all caps anymore.

I was unaware of it but auto traffic has been removed from Vanderbilt Ave. for several hours each weekend. This part of Brooklyn is still several blocks away from Prospect Park. I think “pedestrianizing” and “bicyclizing” parts of auto routes have their part-time place in parts of the city that are “underserved” by parks, but not full-time, as has been done on 34th Ave. in Jackson Heights.

As we get near Prospect Park, historic structures abound. 249 Sterling Pl. (at Vanderbilt) is an historic landmark completed between 1867-1869 with an 1887 addition. When originally constructed, the building served as Public School Number 9: it’s now PS 340.

The PS 9 Annex, 251-279 Sterling Pl., was completed in 1895 by architect James Naughton, as the population had outgrown PS 9 across the street. It was designated a NYC Landmark in 1987 and rehabilitated as artists’ housing by 1990 and more expensive condominiums today.

I have an affection for Prospect Heights; unfortunately it dimmed a bit since my favorite rest stop, the food court Berg’n, ran by my old boss at Brownstoner, Jonathan Butler, was a pandemic casualty. But there are survivors.

I pressed further east to Sterling Pl. at Washington Ave., where another vintage sign awaited, at Tom’s Restaurant. This isn’t the Tom’s immortalized in the Seinfeld show, or by Suzanne Vega in “Tom’s Diner” (that one is at Broadway and W. 112th St.) but it has a history as it’s been family-operated since 1936.

“Tom’s Restaurant, an old-school diner out in Prospect Heights… has been successfully harnessing the power of the free sample since 1936. Open just for breakfast and lunch, Tom’s sweet spot is the weekends, when the restaurant’s standard customer lines up outside on Sunday morning, hungover and desperate to get a meal down to have something to throw up a few hours later while watching the Jets. That’s pretty much the worst type of person imaginable (and is also me, weekly), and Tom’s neutralizes this threat in the only logical way—by giving the people free sh*t. The staff preemptively works the line of patrons with platters of sausage, ham, fruit, cookies, pitchers of water, and cups coffee for all. For free. Take one or take six, because nobody but the person behind you in line is counting or cares”—The Infatuation.

While staggering around Prospect Heights in August 2017, crazed from the heat, I chanced upon a bar called Tooker Alley at the patriotic intersection of Washington Ave. and Lincoln Pl. I looked into the name, thinking it had something to do with England. The answer lies not east but west.

The bar’s name was inspired by the Dill Pickle Club, a Bohemian-style speakeasy and later legit bar, in Chicago between 1917 and 1935, founded by Jack Jones, a member of, and organizer in, the Industrial Workers of the World, a left-leaning trade union of the early-20th century. In addition to its purpose as a watering hole the Dill Pickle was host to one-act plays, poetry readings, jazz dances and opera. “Free thinkers” of the Midwest such as Clarence Darrow, Sherwood Anderson, and Carl Sandburg were patrons, but the club attracted all comers regardless of social standing, notoriety or wealth. In its later years, after the repeal of Prohibition, it became a mob hangout and closed in the mid-1930s.

I brought a tour group into Lincoln Station, Lincoln Pl. just east of Washington, after a Grand Army Plaza tour a few years ago, and liked the chicken sandwich so much, I return when in the area and today I just checked to see if it’s still there. No Diet Coke is offered, so I settled for water.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)