If you’ve ever driven through Baltimore and glanced up at the Bromo-Seltzer Tower, you’ve crossed paths with the story of Captain Isaac E. Emerson—a druggist who turned a simple headache remedy into a glassmaking empire. The Maryland Glass Corporation didn’t start as a grand industrial dream. It started because Emerson kept running into a basic problem: nobody could reliably make enough of the bright blue bottles he needed.

Before any of that happened, Emerson was a young pharmacist trying to make a living. He mixed up his own formulas, experimented with remedies, and eventually came up with Bromo-Seltzer, which caught on almost immediately. Once it took off, the demand for those cobalt-blue bottles skyrocketed. At first he bought them from outside manufacturers, but the supply was inconsistent, and Emerson didn’t like being at someone else’s mercy. Instead of waiting on another supplier, he created his own: the Maryland Glass Corporation.

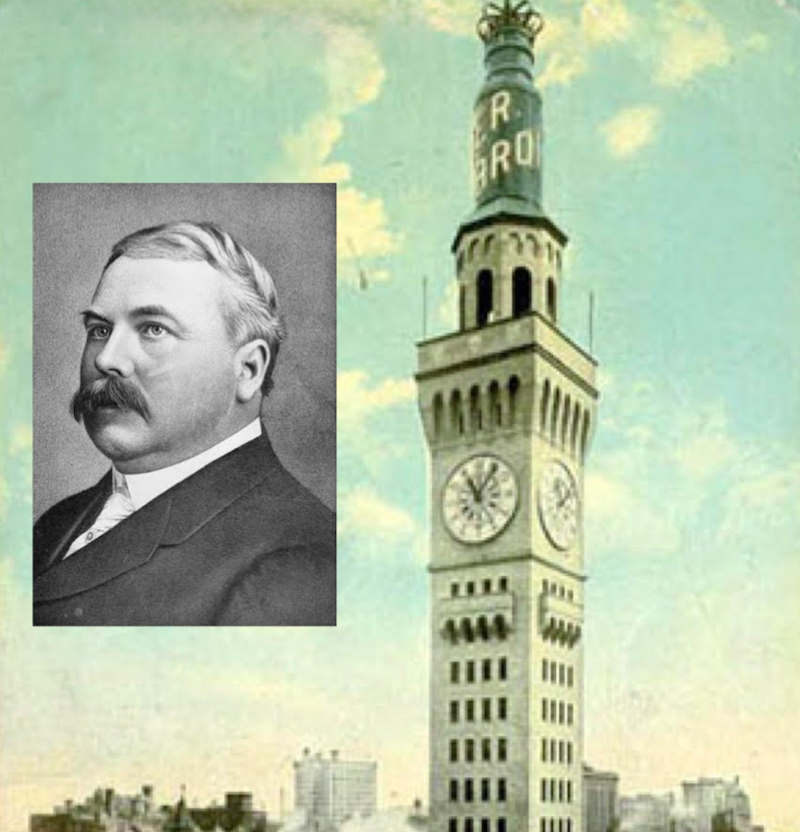

Emerson earned his captain title by organizing the Maryland Naval Reserves and later served as a naval officer during the Spanish-American War. That background shaped how he worked. People described him as decisive, bold, and unusually hands-on for someone running a growing business. The military order carried over into his factories and his marketing strategies. He may have divorced his wife and then built a mansion blocking her view of the Baltimore Harbor and lived in the top apartment “so he could always look down on her,” but on the business side, he got things done and died with an estate worth $20 million.

When Maryland Glass opened in the early-1900s, it wasn’t meant to be a general glassworks. Its first job—and for a long time, its most important—was to make Bromo-Seltzer bottles as fast as customers could empty them. The plant specialized in cobalt-blue glass, which required precise chemistry and consistent firing temperatures. That color, known first as royal blue and eventually “Maryland blue,” became the product’s identity. You didn’t have to read a label; one glance at that color told you what was inside. But the ads heralded the hangover cure: “If you keep late hours for society’s sake, Bromo Seltzer will cure that headache.”

Over time, Maryland Glass made containers for other companies. The plant expanded, modernized, and brought in managers and glassmakers who pushed the technology. What started as a supplier for a medicine cabinet staple turned into one of Baltimore’s most reliable industrial operations. The company became known for its specialty glass—not just the color, but the quality of its molds, the consistency of its materials, and the volume it produced. The company turned out seven million bottles a year, and more than two billion during its tenure. Nearly every blue glass bottle made between 1900-1950 was made at Maryland Glass Corporation.

Perhaps the most iconic building on the Baltimore skyline, the Bromo-Selzer Arts Tower was built in 1911 and initially named the Emerson building, after himself, and modeled after the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, Italy. The majestic 51-ft. illuminated, spinning bottle that once guided ships into Baltimore harbor from atop the building was lit by 596 lights, weighed 20 tons and could be seen from up to 20 miles away, had to be removed in 1936 due to the structural damage resulting from weather. The building now serves as home to artist studios, with a museum dedicated to the cobalt glass in the clock tower.

Like many industrial companies, Maryland Glass eventually went through mergers as the pharmaceutical world shifted. In the 1950s it was folded into Warner-Lambert, but by then it had already shaped decades of Baltimore manufacturing history. The Bromo-Seltzer Tower still stands, and those little blue bottles—the kind people now collect at flea markets and antique shops—are quiet reminders of what Emerson built: a legacy beyond a headache remedy.