“I am really the most controversial artist in the world.” Talented, prepared, and in the right place at the right time, Thomas Kinkade became the most commercially successful painter of the 1990s by mass producing his paintings as “hand-embellished” prints and making the unprecedented move of opening his own stores in hundreds of shopping malls across America. Kinkade, also known by his trademarked sobriquet the “Painter of Light,” successfully leveraged his bewilderment and aggravation towards the fine art world into a multi-million dollar empire, “art for everybody” just a few years before Beanie Babies and Pokémon would provide a more socially acceptable (though no less garish) alternative consumerist obsession for urban liberals eager to pacify their kids. Kinkade’s paintings, lurid and semi-lysergic with their richly saturated colors and touches of magical realism, offered a comforting, even inspiring alternative to the “blasphemous” and “anti-American” works of Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano.

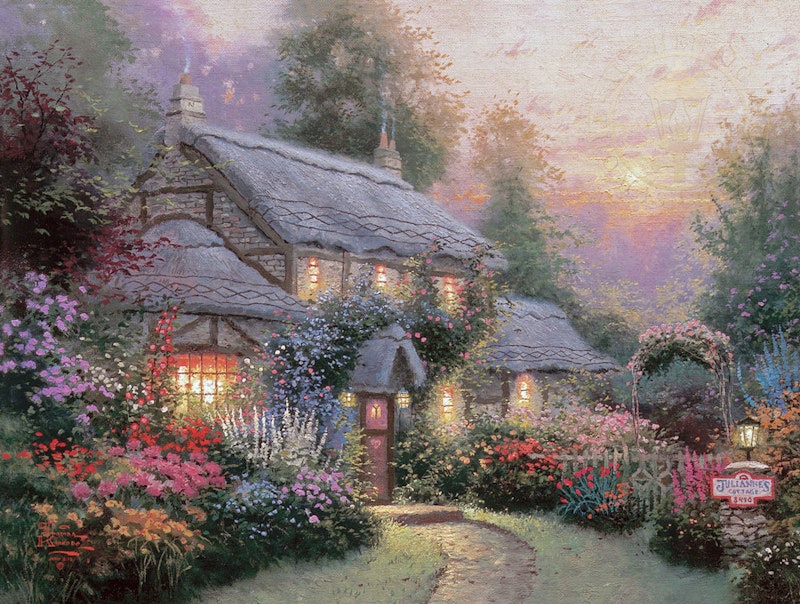

Mapplethorpe’s photography and Serrano’s Piss Christ became cause célèbres at the end of the 1980s; when Kinkade opened his first franchise in 1992, millions of Americans were eager to embrace an artist that they understood and could appreciate. In 2003, Joan Didion wrote, “A Kinkade painting was typically rendered in slightly surreal pastels. It typically featured a cottage or a house of such insistent coziness as to seem actually sinister, suggestive of a trap designed to attract Hansel and Gretel. Every window was lit, to lurid effect, as if the interior of the structure might be on fire.”

Kinkade wasn’t a dilettante, nor an incompetent artist; on the occasion of the only retrospective of his work in his lifetime, Mike McGee of California State University Fullerton wrote, “Kinkade's genius, however, is in his capacity to identify and fulfill the needs and desires of his target audience… If Kinkade's art is principally about ideas, and I think it is, it could be suggested that he is a Conceptual artist. All he would have to do to solidify this position would be to make an announcement that the beliefs he has expounded are just Duchampian posturing to achieve his successes. But this will never happen. Kinkade earnestly believes in his faith in God and his personal agenda as an artist.”

Art for Everybody, a documentary about Kinkade’s life, work, death, and a vault of secret, “darker” works, is in limited release now after debuting at a smattering of film festivals in 2023. The only people interviewed are Kinkade’s family (four daughters and widow Nanette), his business partners, and art critics who dismissed him decades ago and, at the close of the film, are offered a glimpse onto that “darker” work. “He should’ve stuck with it,” Christopher Knight of The Los Angeles Times says. Susan Orlean, whose October 2001 New Yorker story brought Kinkade to the awareness of people outside “the heartland;” he bet her a million dollars there would be a retrospective of his work within his lifetime at a major museum, and when Thomas Kinkade Heaven on Earth made its 2004 debut in Fullerton, Kinkade was eager to collect.

Miranda Yousef’s film is a standard mix of talking head interviews, archival footage, and home movies; the “dark” work is only previewed at the end, with just a handful of pieces shown in any detail. But Art for Everybody remains compelling despite its formulaic structure because of its interview subjects: Kinkade’s family and friends all readily acknowledge he was an alcoholic who crashed and burned in the 2000s, dying at 54 by Valium overdose in 2012; at the same time, they’re all remarkably well-adjusted and clear-eyed, with none of the “tells” of similar talking head exposes. Kinkade wasn’t an abusive husband or father, he really did believe in God and “the light,” and, crucially, he wasn’t a hack. Kinkade believed in his paintings more than someone like Andy Warhol, who nonetheless would’ve respected Kinkade and gotten a big kick of out his mass-produced empire.

But he’d never be accepted or even acknowledged by the fine art world, and that lack of validation echoed his father’s abandonment when Kinkade was only two years old. He may have painted for his mother, but it was the absence of his father, and the ever unreachable reasons why he just didn’t care, that drove him to paint himself into an empire. By the end of his life, separated from his wife and semi-estranged from his children after multiple failed rehab stints, Kinkade took to dressing like Steven Segal: skull rings, hair extensions, motorcycles, and a vaguely Asiatic tough-guy look totally at odds with his cottage paintings but just another cliché you’d find at the mall.

Kinkade was American consumer culture personified: Born Again, but a fan of Big Macs and bourbon; disciplined and ambitious, but naive until the end (at one point, Kinkade says “Wine makes you feel good, how can that be bad for you?”); faithful husband who eventually succumbed to an overdose of legal drugs in the arms of a new girlfriend (“In the last year of his life, he was going through women like water,” says one associate).

Kinkade’s tragic rise and fall is too banal for a David Lynch film, but the similarities in their work are impossible to ignore. By refusing any nuance, subtext, or irony in his paintings, Kinkade invites inquiries and suspicion—but the art world never even granted him bad reviews or reviews of any kind. There’s a similar tension in the cottage paintings and Blue Velvet, and if Lynch had spent his life making mechanical robins for the rest of his life, placid patriotic affect intact, he would’ve been in Kinkade’s class. There’s no reason Kinkade couldn’t have become peers in filmmaking: he worked with Ralph Bakshi on Fire and Ice in the early 1980s, and Bakshi was impressed and got along with Kinkade. He could’ve done matte paintings on Dune. They were obviously aware of each other, but what did they think of each other’s work?

There aren’t many reviews for Art for Everybody, but I’ve seen more than a few compare its subject to Donald Trump. Parlaying your own Oedipal angst into a generalized disaffection and making millions of dollars in the process is an American pastime, and while Kinkade’s often gaudy work and obnoxious personal style at the end of his life echo gold-plated Trump Tower, he crucially did not make it—although this documentary was made in 2022, it’s clear now that Trump won more than just the election. The circumstances of his assassination attempt, how close he came and how he moved his head just so at the spur of the moment—it’s as if he’s been touched by God. By contrast, Kinkade is just another American burnout, probably proto-MAGA, but not “Trumpian,” which should imply some kind of magical force field at this point.

Still, Kinkade’s paintings did appeal to Americans who felt condescended to and, worse, ignored by the people on the coast, the “They” who was always spoken of to, the one who did everything. He wasn’t touched by God, but those cottage paintings enthralled millions, including one woman who told Kinkade, “I’m putting all of my retirement money into this.” Far from bloodthirsty, he looks slightly embarrassed, but nonetheless unable to stop the charade. At that point, you have to believe that you’re not taking advantage of people, they’re just screwing themselves—I mean, how dumb do you have to be, right? But it clearly doesn’t feel good to stand there and sell the lie, live the lie, over and over—no doubt it’s what pushed him over the edge into terminal alcoholism. You reach the top of the world, a millionaire painter, an impossibility even in the 1990s, but the art world still ignores you, and worse, you never had a dad. The end was written into the beginning: even in success, he lived and died like his audience, within the lines.

His literary equivalent is someone like Harold Robbins, whose appetites and activities matched the perversity of his massively popular novels, but “the bestselling author of all time” is forgotten now, and more than a decade after Kinkade’s death, he too is receding; a full exhibition of the early “dark” work would bring him back into the conversation. Why not? He’s not around anymore to respond, and those cottage paintings sold for a reason: they’re pure wish fulfillment, less refined than Disney movies and even less complicated in their messaging: everyone is together, and everyone is happy, and everyone is safe, and everything is wonderful. There’s no narrative beyond that. They are unresolved paintings, not at all un-interesting, and along with the “dark” work, it’s only a matter of time before someone smart mounts a show in New York, London, or Tokyo.

—Follow Nicky Otis Smith on Twitter: @MonicaQuibbits