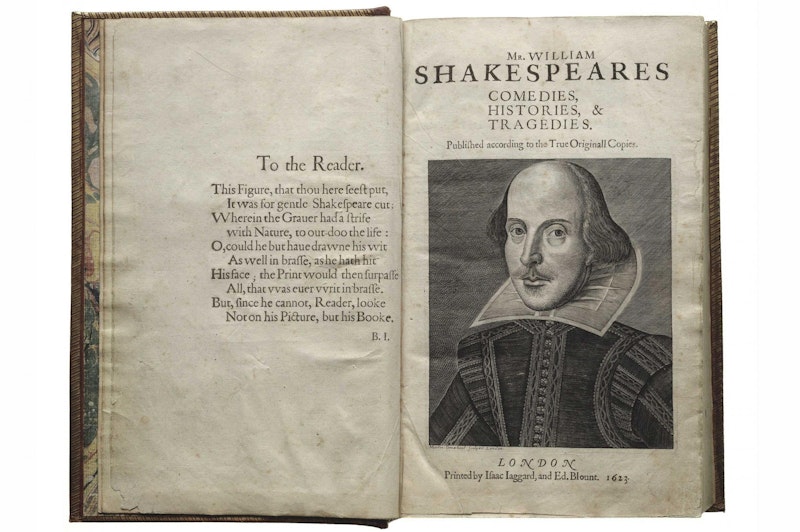

I’ve got this lovely old leatherbound Shakespeare Folio, with his signature on the front and along the spine in gold lettering and the thin paper burnished on the edge with some of that same shine.

In beautifully ornate handwriting on the inside cover there’s a date, November 8th, 1911. There’s a list of names in that same lapidary handwriting that I struggle to make out with my eyes so used to mechanical perfectly reproduced serif computer fonts. The price on the upper right hand corner of the recto in the spindly faded pencil lines of a bookseller reads £6.50—but this pixel pound sign doesn’t do it justice, it’s a big looping “L,” taller than any of the numbers that follow it with two stubby proud little horizontal lines up the middle distinguishing it from the letter (that letter being “L”—how do you describe the quality of an L?).

I think this book was printed in 1906, because that's the year listed at the end of Austin Brereton’s (I haven’t a clue who this is) “A NOTE ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS,” June 1906. There’s a long biographical introduction and an essay by Henry Irving refuting the idea that Shakespeare was Bacon. The nut of that argument is that Shakespeare uses language that only an actor would know to use, such as sneering at too charming by half child actors in Hamlet, and Bacon having never walked the boards himself just could not have had the sense of it that Shakespeare so clearly did. Henry Irving knows this because he was a great Shakespearean actor. Well, that’s what they say. I’ve never seen Henry perform but everyone says he was. The dedication of this volume that I’ve been describing is to him. It reads as follows:

TO

SIR HENRY IRVING

WHO, BY HIS

FINE INTELLECT AND SPLENDID ACCOMPLISHMENT,

HAS, FOR MANY YEARS,

ILLUMINED SEVERAL OF THE GREAT PLAYS

OF

S H A K E S P E A R E

THROUGHOUT THE STAGES OF ENGLAND AND AMERICA,

THIS VOLUME IS, BY PERMISSION, AND AS A TOKEN OF APPRECIATION

OF HIS MAGNIFICENT INTERPRETATION OF

ENGLAND’S GREATEST DRAMATIST,

RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED

Sounds pretty good to me. They say that about Stella Adler’s father too, Jacob Adler, who came from Odessa to take the New York City Yiddish theater by storm. Apparently his Shylock was unmatchable. Yiddish Shakespeare sounds wonderful. I met a man from Israel in Romania who once who told me about reading Shakespeare in Hebrew as we walked the hills above Brașov. They say Jacob Adler is wonderful but I’ve never seen him perform.

There’s some evidence for Henry Irving’s talent though, courtesy of the beautiful illustrations in the book. Many of these are full color prints on heavy glossy paper, and some are black and white photographs of the greatest Shakespearean actors of the age made up and costumed and in character. Irving wears Shylock’s gabardine and his eyes glint and glower with the malevolent cunning that animates the darker side of the Merchant of Venice.

I opened this folio the other night based on an argument I was having with a friend, and by extension an argument with everyone who studies Shakespeare and literature. I maintain that Julius Caesar is a history play, as well as Antony & Cleopatra. My friend, representing the side of Everybody Who Thinks or Writes about this, counters that the only Histories are the English plays, and that Julius Caesar and the story of the Roman & the Egyptian and the Asp are tragedies.

My folio’s biographical introduction confirms this, though it ranks Julius Caesar and Antony & Cleopatra as not just tragedies but Roman Tragedies. An important distinction. I think the characters in both plays are hardly Roman, they are the Roman that is British anyway so I think they should be histories even going by the condition that all Histories must be English. But I’m used to having opinions that would get me thrown out of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

My other point of divergence is my insistence on calling a slice of Shakespeare’s plays Pastorals. I would include A Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, The Tempest, Measure for Measure, As You Like It, and Pericles on this ledger. My folio’s biographical introduction doesn’t include this classification. It calls those plays, largely, Romantic Dramas.

My classification of the Pastoral comes from a mood. There’s a scholarly tradition in calling some of these plays pastorals based on hallmarks of English pastoral romances and similar elements being present in Shakespeare’s work but it’s all far too boring for me to get into and trying to adduce it wouldn’t be honest, because I don’t really base my classification on it. It comes instead from a hazy sort of beauty that I think distinguishes these plays, which are alive with what feels like magic, which aren’t tragic, which are often very funny but soaked with the profound, often recited by a jester. They feel like the countryside even when they aren’t, a walk along a muddy track and then AH, chased by a BEAR! Not to worry, a fool will sing a dreamy song soaked in wisdom and young lovers will live happily ever after, or a young girl will see the world for the first time and declare it brave and new, and there will be an old wizard with a bald pate controlling everything and everywhere with a profusion of vapors and ancient words.