Eleanor Roosevelt supposedly advised: If you don’t have anything nice to say, then don’t say anything. It’s one of the golden rules of social etiquette, the sure way to avoid conflict. However smart in theory, in practice it’s of almost no value. No one trusts anyone who avoids unpleasantness. Unless negative opinions play some part in a conversation, there’s always the suspicion that the speaker isn’t sharing real thoughts.

More realistic is Dorothy Parker: “If you don’t have anything nice to say, come sit by me.” Only when a person is spilling the dirt on someone else is there a feeling of truth in the air. How many times have I been part of a conversation which, beginning with someone being complimented, by the end is a verbal lynch mob?

This principle holds true for all human endeavors. Could it be that the mere recognition of any other person is an unacceptable limitation to our own personal space? “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic” wrote Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. We must be careful not to cause panic, but in doing so, our own world is given borders. What if you feel like shouting fire?

People accept the inconvenience of rules not because they agree with the principles, but because they know that the rules apply to other people. “I can’t do it, but more importantly, no one else can either.” Sometimes the indignation one sees surrounding certain headlines seems false. Consider Jeffrey Epstein and his island. I wonder how many people who criticize it, if they had the chance, wouldn’t have taken the plane? It’s like a joke in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall. His friend, corrupted by Hollywood, says that the night before he’d been in bed with 16-year-old twins, saying imagine the mathematical possibilities. Woody says “Aw, you get tired of that.” I don’t think Woody ever did.

Tolstoy famously wrote at the beginning of Anna Karenina: “All happy families resemble one another; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” No one trusts a happy story; there’s nothing to say. That’s why authors devise diverse ways for torturing their characters. And if the story does have a happy ending, a clever author makes sure the characters have suffered so much that they deserve it.

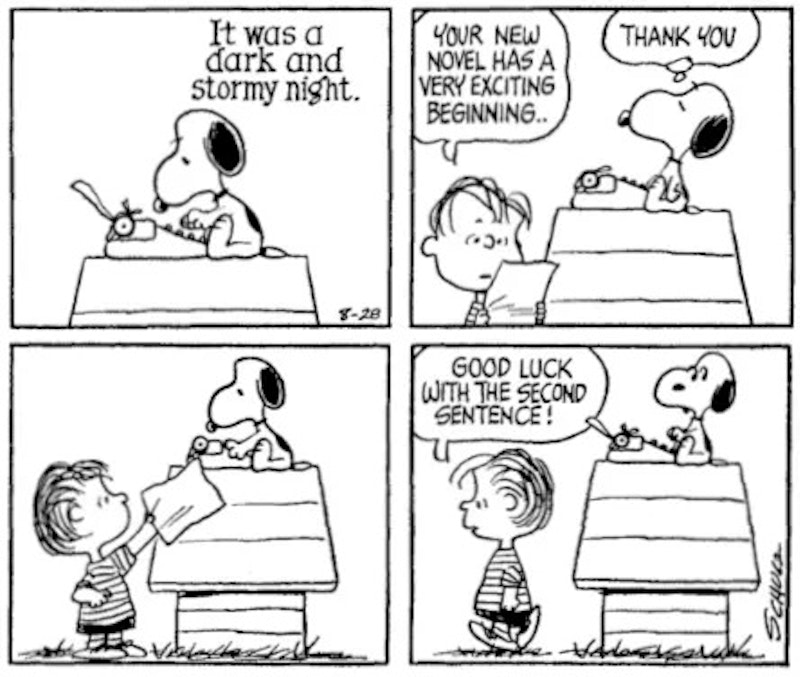

It’s difficult to get artistically inspired by happiness because it’s an unperturbed and balanced state. It doesn’t suggest movement, like watching a smooth stream on a summer’s day. That’s why Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s famous opening line, “It was a dark and stormy night” though a cliché, is such a classic, for intrigue is born of turbulence and imbalance.

Anytime a book starts with a content person, the first question is “What torments lay in store for them?” This was the key to the 19th century-novel, mastered by Balzac. Modern authors became aware of this and developed new strategies. An interesting variation is found in The Castle by Kafka. Instead of directly torturing his character, he places him in confused and constantly redefined situations. He wanders from point to point, doing his best to make progress in an incomprehensible universe with shifting rules.

Perhaps the only real conversational formula which consistently works is agreeing with what the person with whom you are speaking is saying. But this must be done with art or it won’t work either. One must ask them to clarify their point, go into greater detail, seem as interested in listening to them as they are in talking. I had a recent conversation like that. The person spoke uninterruptedly for 30 minutes and I just nodded or agreed. At the end I was told that I was a great conversationalist.

Is this need born from a desire to be understood or simply a desire to control someone else? Like the character Frank Booth says about his captive Jeffrey Beaumont in Lynch’s Blue Velvet: “I can make him do whatever I want.” They’re doing what they like and forcing another to accept it. Does it make sense? Is it graceful, useful, productive? No matter, it’s them and that’s enough. But, if they’re civilized, after they have cried “fire!”, then they’ll allow you to have your say, just don’t get carried away.