The Bayonne Bridge, opened in 1931, provides a picturesque backdrop for many of Port Richmond, Staten Island’s east-west streets. The bridge has a walkway, which I first used in the summer of 2012. I return to Port Richmond relatively frequently—it’s New York City’s version of one of those innumerable small towns around the country whose downtowns have been Wal-Marted to death, as described in James Kunstler‘s sociological-urban studies books such as The Geography of Nowhere. Port Richmond embodies Kunstler’s manifesto. Kunstler says he wrote The Geography of Nowhere, “Because I believe a lot of people share my feelings about the tragic landscape of highway strips, parking lots, housing tracts, mega-malls, junked cities, and ravaged countryside that makes up the everyday environment where most Americans live and work.”

Staten Island’s North Shore once employed thousands along its docks, factories, shipbuilding plants and factories. The nation’s supply of Ivory Soap was once made in Port Ivory, just a mile or so west of Port Richmond. Those workers and their families had homes in places like Elm Park, Livingston, Mariners’ Harbor and Port Richmond. They shopped in stores along Richmond Ave. such as Lobell’s and attended vaudeville shows, movies and much later, rock concerts at the Ritz Theater. They caught the ferry to the city by riding the North Shore branch of the Staten Island Rapid Transit.

The factories and docks were closed, the railroad was shuttered in 1953, and by the time I discovered Port Richmond via a bus from Bay Ridge in the 1960s after the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge opened, things were already going downhill. The opening of the Staten Island Mall in 1973, a short distance from Port Richmond by bus (Staten Islanders, unlike the rest of New York City, had relied on cars as early as the 1920s) greased the skids and Port Richmond ceased to be one of the island’s main hubs.

It’s a neighborhood of ghosts.

Though many of Port Richmond’s industrial businesses didn’t make it out of the 1970s, H.S. Farrell Lumber and Millwork survived to 2009, occupying several buildings on Richmond Terrace, including the double-towered former Empire Theater, open for its original purpose until 1978, though it spent its final theater years as a porno palace. The “raincoat brigade” was replaced by a great deal of wood, in H.S. Farrell. Ultimately, a storefront church has claimed the space.

You might not associate Aaron Burr with Staten Island. However, he did live on the island, on Richmond Terrace just north of this lengthy brick building on the east side of Port Richmond Ave. between Richmond Terrace and Church St. It was built in 1874 for Charles Griffith, a boot and shoe dealer. Directly abutting it on Richmond Terrace was an 18th-century private residence, in its later days called the St. James Hotel, known to be the last home of Burr before his death; that building was demolished in 1945.

Across the street, on the west side of Port Richmond Ave., are a pair of buildings likely built in the 1880s that were associated with the Staten Island National Bank. A ghost sign on the Port Richmond Ave. side advertises a former connection with the Chase Manhattan bank. I zoomed in on the old burglar alarm and night depository slot. Another ghost sign on Richmond Terrace indicates it was once a drive-up bank as well. According to bank history site Scripophily, Staten Island National Bank was established in 1902 as the Port Richmond National Bank and merged with Chase in 1957. The website Ape Shall Not Kill Ape has a couple of vintage photos of the building.

These fake ads fooled me at first. If the ancient buildings and abandoned downtown weren’t spooky enough, this stretch of Port Richmond Ave. has been characterized in the past by superannuated awning signs of long-vanished businesses, so I thought that these were similarly ancient and had been uncovered. But they were relatively new and were placed there as props for a film shoot, since shows like Boardwalk Empire have filmed extensively on the island; Empire props left in Richmondtown for a couple of years were similarly convincing.

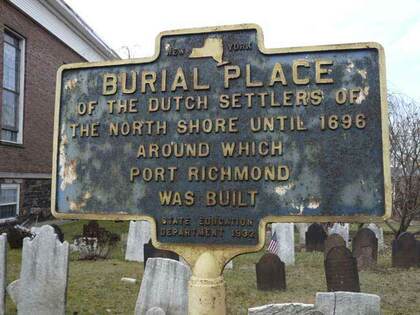

Dutch Reformed Church Cemetery, established in 1696, is the oldest burial ground in Staten Island, and is in the Top 10 oldest in the city; Prospect Cemetery in Jamaica, Queens (1668), downtown’s Trinity Cemetery and the Shearith Israel Cemetery on St. James Place in Chinatown are also on the list. (Gravesend Cemetery [1650] is the oldest, says historian Joseph Ditta.) Originally it was the private burial ground of the Corson family, which owned a great deal of what became Port Richmond in the early colonial days. Interments continued in the cemetery until the city banned further ones on a spurious health basis in 1910. Family members of previously-owned plots continued to be buried there until the 1930s. The oldest remaining gravestone is from 1746.

To read the cemetery headstones is to read a street map of Staten Island, with Corsons, Crusers, Van Names, Burghers, DeHarts, Haughwouts, Latourettes, Mersereaus, Zeluffs, and numerous other families represented. In the colonial era Staten Island was settled by the Dutch and later by Belgians of French extraction known as Walloons and also by French Protestants known as Huguenots who were expelled from France due to their religious choice.

Several veterans of the American Revolution are here, including Major William Gifford (1750-1840) an aide de camp of George Washington. His grave’s under the sidewalk in front of the adjacent Dutch Reformed Church, a Greek Revival Staten Island Reformed Church constructed in 1844. Brown sandstone monuments from the 18th century feature older death’s head apices but also the latter-day ones with more cheerful cherub tops. Some are in the Dutch language, though not as many as at the Flatbush Dutch Reformed Church, which also originated in the 1690s. Ironically, the older sandstone gravestones are more easily read than the later ones in marble, that succumb more easily to rain, wind and pollution.

The former Ritz Theater, Port Richmond Ave. and Anderson St. opened in 1924 and was employed as a movie theatre, concert venue, and roller skating rink till 1985, when it was converted to a bathroom tile showroom. The Ritz, according to legend, launched the career of Jerry Lewis, who did a comedy act here in 1942 and was signed to a motion picture contract soon after.

From 1970 to 1972 the Ritz (which held 2126 seats)—and other “outer-borough” venues such as the Loew’s 46th Street Theatre (renamed the 46th Street Rock Palace) in Borough Park, Brooklyn, where the Grateful Dead played 2:30 Wednesday afternoon matinees—featured some of the world’s biggest rock bands at the height of their popularity.

Alice Cooper, Badfinger, Captain Beefheart, Black Sabbath, Iggy and the Stooges and Deep Purple all played the Ritz in the early-1970s, when they were touring behind such albums as School’s Out, Straight Up, Paranoid and Machine Head. Other bands that stopped by the Ritz were the MC5, Mountain, the Allman Brothers, Edgar Winter, the Kinks, Yes (the last two a double bill), Humble Pie, King Crimson, Uriah Heep, Canned Heat, the Chambers Brothers, Three Dog Night, the Hollies, and a post-Jim Morrison Doors. The shows were booked by brothers Arnie and Nicky Ungano, who also had their own concert venue, Ungano’s, on W. 70th St. on the Upper West Side.

At Post Ave. and Driprock St. in Port Richmond you’ll find this formerly grand brick structure, with Corinthian columns and arched windows, most of which have had plywood affixed to them.

The building has served many uses over the years. It was constructed as Svea Hall, which served Swedish immigrants and other Scandinavians who found work in the former shipbuilding concerns along Richmond Terrace or loading and unloading imported goods from the Brooklyn waterfront (those without cars could get to Brooklyn via the St. George ferry to Bay Ridge, which will be revived in December 2025). Though Swedes were outnumbered by the Norwegians among Scandinavian immigrants, they made their mark in Staten Island, from the grand Swedish Home for the Aged in Sunnyside (demolished over a decade ago) and Svea Hall, which afforded financial services and provided news from the old country and provided a place to meet and chat in the old language.

After several decades Svea Hall became a Masonic lodge and in its later years, a center for Staten Island’s Alzheimer’s Foundation. Today, the building hosts Yeshivas Nehardue, an institution for advanced Jewish religious studies.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)