When you read Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If…”, you can read it as a prescription for manhood. Many people have had it framed in glass, and prominently mounted, after reading it precisely that way:

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you

But make allowance for their doubting too…

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And – which is more – you’ll be a Man, my son!

But you can also read the poem through its parade of contraries, and learn from that in and of itself. Perhaps, especially since the poem has female as well as male readers, this is the better way. Being happy in this world has everything to do with accepting what the French writer Jean Genet called “the coincidence of contraries.” The poet Antonio Machado put it another, equally compelling way: he said he was never closer to believing one thing than when he was convinced of its opposite.

Consider, for instance, the way the mind works. I’ve recently begun watching Black Mirror on Netflix and thinking, as a result, about the meanings a work of horror can possess. There’s an episode in which a woman downloads her consciousness into a flash drive, to put her doubled consciousness to work as her own personal slave. Her downloaded consciousness becomes responsible for setting alarms, making toast, turning off the lights, and everything else she likesa certain way but doesn’t want to do. As a download, her consciousness has no rights or privileges. But as a consciousness, it’s violated. She screams and begs to be let out of her featureless virtual prison, but since the other, embodied version of herself is paying for the service, her captors simply wait for her to comply.

Like all good science fiction, this isn’t merely a “scarily possible portrait of what the future may bring.” It’s already the way we treat our consciousness. How many people eat “brain food,” or play Lumosity, in the hopes of stimulating themselves to some undreamt-of new height? How many of us drive our thoughts, like hapless oxen, through one self-help paradigm after another? How many of us force ourselves to carry out routines that seem comforting, but are really little deaths? The triumph of the superego looks deceivingly productive and organized, when we internalize socially conditioned goals and rules for ourselves, and make slaves of our own complex, unfathomed inner lives.

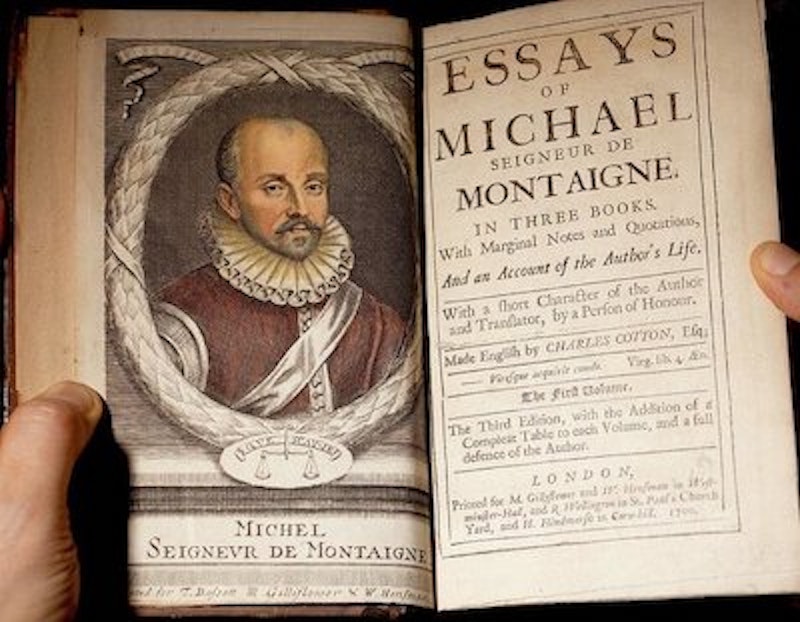

Writing about the difference between spontaneous and planned speech, Montaigne comes to a similar conclusion: “I know from experience the kind of character which gets nowhere unless it is allowed to run happy and free and which by nature is unable to keep up vehemently and laboriously practising anything beforehand. We say that some books ‘stink of lamp-oil’, on account of the harshness and roughness which are stamped on writings in which toil has played a major part. In addition, a soul worrying about doing well, straining and tensely drawn towards its purpose, is held at bay… I discover myself more by accident than by inquiring into my judgement… something subtle springs up in me as I write.”

Everyone who writes or meditates knows what Montaigne is describing. Sometimes, as a fiction writer, I feel like the only point of the preconceived notions I generate about my stories and characters is that they allow me to sit down and write until I can discard them entirely. One’s consciousness ought not to be a slave, but a person, deserving of respect and even awe. We ought to treat ourselves as delicately as an unsuspected flower that turns up underfoot.

And yet… the triumph of the subconscious is no great feat either. We know that W. B. Yeats dabbled in automatic writing, but it was Yeats who wrote:

A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.

He values the appearance of spontaneity but achieves it through determined labor. He refuses, at his best, to stand back and marvel dumbly at his own mind and its dreams. As recently as Monday I repeated a comment I’ve often made, to the effect that stupid horror movies can be scarier than smart ones. After watching Black Mirror, though, I realized I was wrong. My primary example of a stupid horror movie, Event Horizon, is actually a very acute portrait of the way drugs, trauma, and obsession can up-end the soundest and most virtuous personalities, suddenly and completely. What really scared me about the film was that I hadn’t realized what, in the real world, corresponded to its dark fantasies. Without an explanation for it, I was at its mercy, isolated by my fears and associations. Meanwhile, the movies I considered “smart” horror, like The Silence of the Lambs, were really just stories I could translate more easily into universal terms.

The mind is its contrary moments; that is Kipling’s revelation. We are the stories we contain within us, without suspecting they are there, or grasping how they cohere. We are also the explanations of those stories, slowly and painfully worked out. As a solipsistic fantasy, unconstrained by understanding, every story becomes a horror story. But the moment we fully comprehend an artwork, and explain it, something free and unprecedented about it slips away. As readers, and writers, and artists of our own lives, we thrive on the argument between the imagination and the understanding, between the Earth and everything that’s in it.

—This essay was inspired by Michel de Montaigne’s tenth essay, “On a ready or hesitant delivery.”