You can’t find Gaye Clark’s post about accepting her black son-in-law. “It’s been replaced on the blog with a recording of a conversation between three African-American men,” Vox tells us. Vox misses something: one of the men is an editor at the blog in question.

The place is called "The Gospel Coalition," and Jason Cook says that before publication he read the article “through a couple of different lenses.” He also says the article was shown to Mrs. Clark’s daughter, her son-in-law and “multiple African-Americans and people of color.” The verdict, he says, was that the piece “was very helpful, it was beautiful.” But then came publication and social media outrage. As a result, Cook sat down with his co-religionists Isaac Adams and Jemar Tisby, and they spent an hour talking out the implications of Mrs. Clark’s now-deleted piece, “When God Sends Your Daughter a Black Husband.” Vox should give them a listen.

Adams, Tisby and Cook don’t attack their co-religionist, but they do fault her. A non-believer might think Mrs. Clark’s account fell straight in the Christian tradition of “I was blind but now I see.” A person starts out dumb, and by prayer and self-struggle the person becomes less dumb. “As you pray for your daughter to choose well, pray for your eyes to see clearly, too,” Mrs. Clark wrote. “Glenn moved from being a black man to beloved son when I saw his true identity as an image bearer of God, a brother in Christ, and a fellow heir to God’s promises.” But the three Christians have their problems with the piece. For example, the kickoff: “This white, 53-year-old mother hadn’t counted on God sending an African-American with dreads named Glenn.” God “sends” cancer, one of the fellows points out. Another (or I think it was another) says that mentioning the dreads seemed meant to play up Glenn’s blackness and strangeness. The consensus is that the piece came across as advice for people coping. “Eight Steps to Accept a Black Person Into Your Family” is a phrase that comes up.

One of the men is provoked by this quote: “Calling Uncle Fred a bigot because he doesn’t want your daughter in an interracial marriage dehumanizes him and doesn’t help your daughter either. Lovingly bear with others’ fears, concerns, and objections while firmly supporting your daughter and son-in-law.” No, the man says. “That is a jagged pill to swallow for a minority because we are patient, all the time, every day, with racism,” he tells us. “And to encounter this in the family that you’re going into—you know, for Glenn’s sake, I think, we need to confront that stuff boldly, and if the bigot in your family is offended, I think that’s an offense for the Gospel.”

Meaning that the bigot should suck it up and deal with his sin being denounced out in the open. But why “boldly” and not “firmly”? The woman doesn’t say smile and pat Uncle Fred’s hand. She’s all for telling Fred he’s wrong. But she doesn’t want him to be called names and treated as a pariah. Her view is Christian, I’d have thought, and the quote we have doesn’t say anything about Fred’s hating anyone. He’s against the marriage and has “fears, concerns, and objections.” No doubt these are misguided—unless he’s worried about the husband being hassled by police and stiff-armed by banks—but how bad is Fred himself?

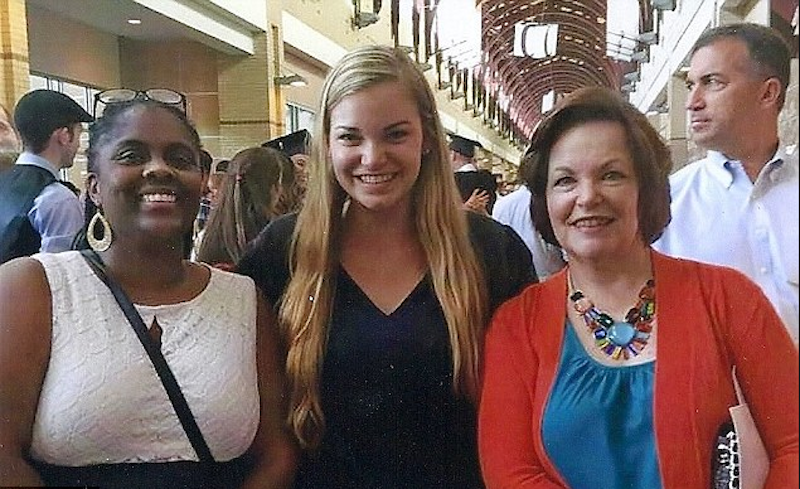

Damn bad, says Vox. “It’s important to her that racist relatives get the compassion she says they’re due,” the site’s article says of Mrs. Clark, whom it considers “unevolved.” Vox, being evolved, sneers at compassion. Summing up the article’s crimes, Vox says Mrs. Clark “managed to highlight the intensity of the bias against black people in the author’s community.” True, her piece did that. I say take a look, and while you’re doing so, size up Mrs. Clark as well. “God called my bluff,” she wrote after recalling her many prayers for a hard-working, decent, Christian son-in-law. God sent her Glenn, who was all these things plus black, and she just had to adjust. If you’re surprised adjustment was necessary, you don’t know white America. If you think that Mrs. Clark’s changing of her own attitudes doesn’t count as an accomplishment, you don’t know much about people.

Looking back, Cook says the blog should’ve had Glenn’s mother write the article with Mrs. Clark. This would have “decentered” the piece, he says. But decentering is a bust when it comes to articles. Turning the mothers into a two-person committee means hearing only those things that they both want to say. I’d rather hear everything that’s on their minds, not the overlap. The result will be a white voice and a black voice, not an everybody voice. As Mrs. Clark has shown us, a white voice can be alarming when talking honestly, especially about the interracial marriage of the speaker’s child. A black voice might be too. But I’d rather know. How bad are most people, after all?

—Follow C.T. May on Twitter: @CTMay3