“It’s all complicated, and it’s all connected,” Roger Penrose, Oxford theoretical physicist, told his biographer Patchen Barss in the first interview, in 2018, that would lead to Barss’ fascinating upcoming book, The Impossible Man: Roger Penrose and the Cost of Genius (Basic Books, Nov. 12). Penrose was conversing on cosmology, AI, music, chess, his mother’s death, and more, while fiddling with a tetrahedral puzzle he’d designed. He mentioned he was recently separated from his second wife; living alone for the first time in decades, he said it gave him more time for research. Estrangement from family is a sad theme of the book. Penrose won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2020, for his 1960s “discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity.”

Penrose’s wide-ranging work has fascinated me. In 1990, when I left my job at a bank technology magazine, I may have missed a deadline for COBRA because I was engrossed in Penrose’s book The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and the Laws of Physics. I became aware of Penrose in the early-1980s from mentions by Martin Gardner, who had publicized non-repeating Penrose tiling; in a review of “Seven Books on Black Holes” (none by Penrose), Gardner described “a bizarre mathematical entity” Penrose had invented, twistors, as “sort of halfway between particles and pure geometry.”

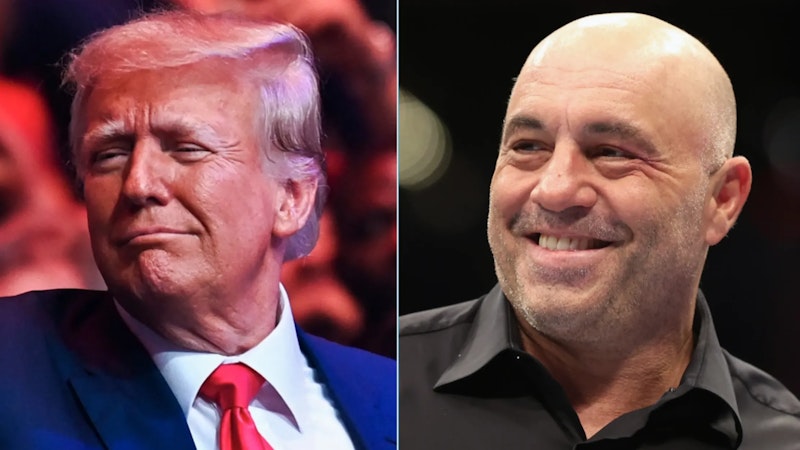

Penrose is a true practitioner of “the weave,” a term Donald Trump has lately used to exalt his own shifting among topics. Notwithstanding my criticisms of Trump, I’ve an affinity for the weave, in aspiration if not outcome, as I contemplated in Trump’s appearance on Joe Rogan’s podcast.

Trump segued from a discussion of releasing files about JFK to the possibility of extraterrestrial visitation. “I'm going to do it [release JFK files] very soon. There’s a lot of interest in it. One of the things that a lot of interest in the people coming from space, you know?” Trump said, glancing upward.

Trump said he’d only a “little interest,” not a “great interest,” in this topic, but has interviewed fighter pilots who’d said: “We saw things, sir, that were very strange, like a round ball. But it wasn’t a comet or a meteor. It was something. And it was going four times faster than an F-22, which is a very fast plane. And it was round, which is, in theory, a great shape.” Using a triple negative that seemed unintentional, Trump said: “There’s no reason not to think that Mars and all these planets don’t have life.”

Rogan: “Well, Mars, we’ve had probes there and rovers, and I don’t think there’s any life there.”

Trump: “Well, maybe it’s life that we don’t know, but maybe it’s a different kind of life.”

Rogan: “Well, maybe there was life there at one point in time. This is a speculation about Mars, that Mars had an atmosphere at one point in time a long time ago that could support life. It also had large bodies of water, but we’ve had no evidence of even bacterial life that exists on Mars.”

Trump: “But the universe is pretty vast. It’s not been a big thing for me. I mean, when I looked at what China did to this, they would have never done it with me, where they put the balloon up, and a lot of people thought for a little while that that was one of these things.”

That discussion of extraterrestrials struck me as more coherent than some, though the leap to the Chinese balloon was dubious, especially as such balloons flew over the U.S. during the Trump years.

Soon after Trump went on Rogan, I attended an event at the Simons Foundation, “Imagining Other Worlds,” in which astronomer Megan Bedell and artist Ari Melenciano discussed exoplanets, worlds beyond our solar system, and more broadly the universe in science and imagination, moderated by Samir Patel, editor of the excellent online magazine Quanta. Bedell’s research focuses on exoplanets, and particularly on finding any that are similar to Earth; that’s not easy, as astronomical techniques are better-suited for finding larger planets such as “hot Jupiters,” gas planets close to a star. (Note: I’ve copyedited for the Simons Foundation, but my current involvement is limited to attending free events.)

Bedell noted that hot Jupiters are tidally locked to their stars, showing the same face rather than rotating, much like how the moon presents one side to Earth. She pointed out about tidally locked worlds: “There must be a gradient between hot and cold,” a moderate zone between the extreme temperatures of the two sides of such a planet. Bedell’s work isn’t focused on finding aliens, and science is “far from finding alien life,” in her view. Even if the study of exoplanets revealed biosignatures, conditions indicative of the presence of life, this wouldn’t tell us whether that life is intelligent.

“I don’t think it’s a hostile universe out there,” Bedell said, adding that “fears of war and conquest” are “extrapolations from our world to the universe.” Melenciano took a similarly upbeat view. “It’s important to have the agency to think of ourselves as the designers of our own futures,” she said. Melenciano’s worked on an art and book project titled Black Metal, inspired by Afro-Futurism. It involves an imaginary element, and when people wonder if it’s an “anti-white thing,” she encourages a broader sense of possibilities.

At a reception afterward, I spoke with another exoplanet astronomer, a young woman originally from Beijing. She chuckled at my lines of Mandarin, and gave an insider view of the process of selecting observational targets and getting them considered for time on ground- and space-based telescopes.

—Follow Kenneth Silber on X: @kennethsilber