Pat Conte’s 1990s anthology series of world music from the early-20th century was titled The Secret Museum of Mankind, suggesting alchemical, hermetic, and hidden knowledge. The truth was that the wonder of the series wasn’t its obscurity, but the opposite. These were all commercial discs, recorded by performers who were reaching out beyond their village or niche to a broader audience—perhaps to people longing for the sounds of home, or perhaps to collectors seeking out new or unfamiliar sounds. Conte, as curator, unearthed gems, but they were gems that’d been put out there for collection. The secret here was that these weren’t secrets, but public effusions—a proliferation of sound and genius, created not for a few people alone, but for all.

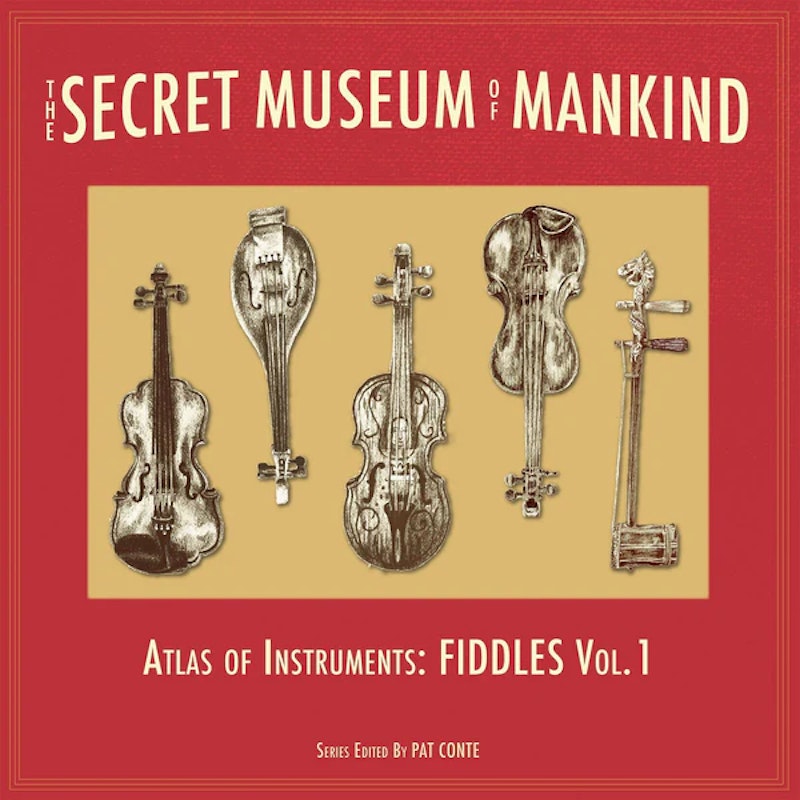

A couple of decades after those first discs, Conte’s back at it, this time with a series of recordings organized by instrument. A volume on guitars came out in 2021, and last year Conte released Secret Museum of Mankind: Atlas of Instruments: Fiddles Vol. 1. The collection is 49 minutes and includes 18 songs, every one a joy.

Some of the selections are in styles that’ll resonate with any roots music enthusiast; English fiddler Jinkey Wells’ “The Maid of the Mill” and Paddy Killoran’s “Sligo Maid’s Lament/Trip to the Cottage” both are recognizable folk tunes, setting feet tapping in a jig on the long dirt road towards Charlie Daniels somewhere in the future. Fiddlin’ Jabe Dillor of Mississippi gets a dirtier sawing sound on “Brown Skin Girl,” and the Mobile Strugglers “Fattenin’ Frogs” is a slow jug-band stroll with a tough, harsh vocal whose echoes foreshadow Howlin’ Wolf, Bob Dylan, Iggy Pop, Eddie Vedder, and many another retro blues rasper to come.

Other selections bow farther afield. Orchestre de M. Michel Ratsimba is a Madagascar band, with the fiddle accompanied by a valiha aka tube zither, an instrument made from bamboo which creates a sprightly sound reminiscent of a mistuned ukulele. From China, San Chi La and Shim Yi Chu perform “Sam Liang Gow,” on huqin, two-stringed fiddles which make a honking noise more like a horn than a traditional violin. Ugandan Abadongo Abaganda performs “Okukomawe,” a breakneck effort in which the rapid rush of the tube fiddle becomes a second percussion instrument along with the drum, creating a polyphonic texture Steve Reich would envy.

Whether they fit easily into current genre expectations or not, though, the recordings are united not just by the bow, but the musician’s expectation that someone is listening in. Many of the recordings, like Quebecois fiddler Joseph Allard’s “La Reel Du Pendu” or a “Danza De Matachines” by an anonymous native Yaqui group, are intended for dancing. Other numbers seem designed to be marveled at, like Gunnulf Borgen of Norway’s “Ingletveiten,” an intricate tune with multiple interweaving melody lines—a virtuoso display that recalls the ornamented Texas fiddling of Eck Robertson. Still others, like Tiramakudalu Chowdiah Mysore’s gloriously droning “Thanam II,” seem like they could be meant for dance or listening.

Folk and world music enthusiasts often will decry commercialization, and the way that the process of recording removes music from its original context, creating a kind of inorganic community unbounded by shared experience or understanding. But Conte’s volume reminds us that there’s a marvelous cosmopolitanism in that inorganic cacophony, as people from every continent come quick stepping out of any one context, drawing those notes out into the ears of anyone who happens to hear them. Atlas of Instruments: Fiddles Vol. 1 sounds like every musician in the world trying to one up each other. That’s a testament to Conte’s curation skills. But it’s also made possible by the fact that all these different performers, from all these different traditions, separated by distance and language, were united by the instrument they played and a desire to be heard.