In 1985, David Bowie took the stage at Live Aid, then the biggest charity concert in world history, to perform “Heroes,” a song which would become one of his most famous and enduring tracks. Forty years on, here’s the story of how an African folk tale drawn from a rare, forgotten book helped inspire Bowie’s lyrics behind the song.

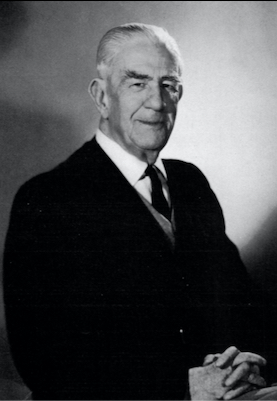

Alberto Denti di Pirajno

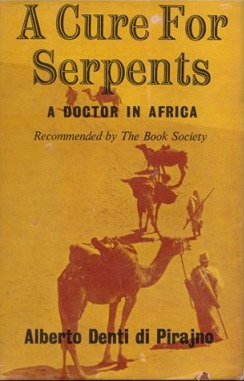

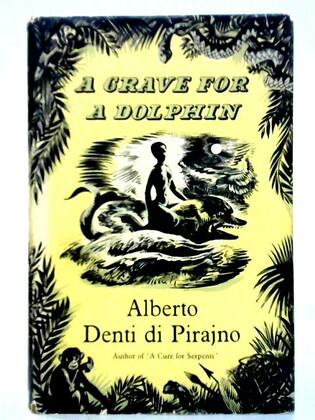

A Grave For A Dolphin was first published in 1956; a non-fiction memoir written by Dr. Alberto Denti di Pirajno, an Italian duke who served as a colonial official in the Italian-occupied territories of Eritrea, Libya and Somalia in the years spanning the two World Wars. The sequel to his first book, A Cure For Serpents (1955) subtitled “A Doctor in Africa,” both books recount his experiences managing Italian interests in the territory, while also giving medical aid to local people. Veering away from the standard memoir format, Pirajno also records many of the folk tales told to him along the way, giving his books an air of magical realism, where strange narratives of anthropomorphism and unusual happenings soon merge everyday oddities, such as his adoption of a lion cub, named Neghesti.

A Grave For A Dolphin sits at the heart of Pirajno’s book, and like Bowie’s title track for the “Heroes” album, comes to define the whole. It’s a story within a story, told first by Pirajno’s close friend, the pearl-merchant Omar Bazra, and also by the tale’s protagonist himself, an Italian army officer named Camara. Known to the locals as “Huto.” It was said that he could swim alongside the sharks without ever coming to harm, even thinking himself a shark. Pirajno mentions that Omar Bazra professes a jealousy towards this ability to swim peacefully throughout the sea, while his own pearl divers and trawlermen were everywhere under threat.

Camara meets a beautiful young African woman, Shambowa, who arrives at his shack at Barrida, a posting near the coast of Djibouti while he’s working on fishing boats to survey the area. She comes to him covered in filth and dressed in rags, and in desperate need of help, having just escaped from slave traders. He quickly discovers that this woman who appeared to have walked out of the desert is not all she seems and that despite their different cultural backgrounds they have more in common than he might expect.

Camara is amazed that Shambowa can swim better than he can, holding her breath underwater for unnaturally long stretches of time. Pirajno includes a photograph of her, he describes a voluptuous black body, shining wet from bathing, wearing only a coy smile and glancing at the photographer we’re told is Camara. Her look, equally coy and knowing, suggests a kind of inevitability that she and Camara would become lovers, perhaps from their shared love of the sea, or a more sudden connection.

Omar Bazra discloses to Pirajno that she must be a kind of djin, in traditional folk tales a supernatural creature which crosses the divide of human and spirit worlds, in Bazra’s view as a Muslim, she appears as a kind of she-devil. Pirajno willingly absorbs the rich seam of apocryphal legend passed onto him during the conversation which highlights the clash between mystic superstition and religious conservatism across African cultures.

Shambowa’s air of vulnerability is dispelled, when Camara sees her too playing fearlessly among the sharks. She brushes them off as “blind uncles,” her brothers from a previous life, and later accepts a ride from a dolphin, another kindred spirit of the sea. Camara watches her clinging to its dorsal fin as it leaps in great arcs through the water. Camara’s struck to see the image of a girl astride a dolphin, drawing him back to a reflection of Taras, the mythical founder of his hometown, who was depicted riding a dolphin on the coins minted by the first settlers to arrive there in the time of ancient Greece. Pirajno indulges this ferment of serendipitous chance giving himself over to the tale’s earnest romanticism.

The next day, Camara awakes to find Shambowa has died from a sudden fever in the night, she’s buried in a grave of piled stones in the tradition of the local Danakil tribe. The next morning he awakes to the sound of cracks, groans and cries to find Shambowa’s dolphin struggling onto the beach in a pool of blood, mortally wounded, arriving at the final tragedy threatened by the book’s title. The dolphin’s buried in a grave, side by side to Shambowa; it’s only then that Camara realizes what he has lost in her death.

Years later, David Bowie would meet his future wife, Iman Abdulamjid, a Somalian-born model who’d found success in New York during the 1970s, on a blind date in 1990. In a 2021 Vogue interview Iman mentioned their shared love of A Grave For A Dolphin: “This is a very fantastical journey between a girl—and you won’t believe it, but a Somali girl—and a dolphin. And this book is really special because, funny enough, way before David and I met, this was one of his favorite books. And actually, he told me that some of the lyrics from his song ‘Heroes’ were actually inspired by this book. And then of course, finally when we meet, we can’t believe that we both adore the same book.”

In his introduction to Iman Abdulmajid’s 2001 book, I Am Iman, Bowie reflected on the story’s spirit, alluding to the symbolic power of dolphins representing the transcendent power of love, which he’d coin in the “Heroes” line: “I wish I could swim/Like dolphins can swim.”

As much as “Heroes” is defined by the image of the lovers kissing by the Berlin Wall (who may or may not have been producer Tony Visconti and backing singer, Antonia Maas), the figure of the dolphin, and its sad fate in Pirajno’s book, gives the song much of its romantic verve. The original story’s tragic ending feeds into “Heroes” underlying sense of self-doubt, much like the cynical shadow of the Berlin watchtower which haunts the lovers as shots are fired overhead.

“Heroes” wears a hard-won pessimism on its sleeve, the singer paints himself into a corner as half-drunk and equally defiant with it. Admitting “I’ll drink all the time” while he raises his beloved to the level of a queen, in his equally dazed partner he prefigures a sense of shared doom. Bowie’s lyric admits that “nothing will help us,” perhaps a sign he’d given up, or an admission that a kind of negative capability, a freeing emptiness is necessary to move on. For Bowie, this would become a continued struggle to return from the “rock bottom” phase of cocaine and alcohol addiction, coining the near-terminal turning point at which many ex-addicts note that their lives truly changed into a time of ongoing recovery.

Bowie’s attachment to dolphin imagery as an emblem of pure freedom endured throughout his romantic and family life, and his ideas of spirituality and sobriety. In 1992 Bowie got his first and only tattoo. Inked on his left calf, it shows his own drawing of a woman riding a dolphin holding a frog in her hand, alongside Iman’s name and a Japanese translation of the serenity poem: ”God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Bowie revealed the tattoo on television during a 1993 interview with Arsenio Hall, explaining his own commitment to sobriety and the further meaning behind his chosen imagery: “I think the Serenity Prayer is something that keeps me back onto that course, very much so, yeah. I was very lucky.”

Standing as an anthem of self-liberation and the defiance of love against the odds, “Heroes” would experience a sort of homecoming when Bowie performed the song in 1987 for a show outside Berlin’s Reichstag. This was the city where Bowie first sought exile from the dogged fame of Ziggy Stardust and the idea of “being David Bowie.” Ultimately this reconnection with everyday life would eventually save him from the shadow of addiction but also enable him to find personal happiness beyond creative success.

“Heroes” is perhaps Bowie’s most personal song that nonetheless carries universal resonance for hardcore fans and casual listeners alike, set against the cruel tragedies and coincidences of life that can make even love seem doomed and hopeless, it remains an enduring anthem of hope and resilience.

—Adam Steiner is a writer working on street-art culture, music, architecture and poetry-film—based in London and Coventry.

His book: https://adamsteiner.uk/silhouettes-and-shadows-david-bowie-book/