One of the most perfect images in John Ford’s filmography—not a single shot, but an environment—is the unfinished church in My Darling Clementine (1946), which manifests itself as an elevated, open stage emerging out of the desert. There’s no facade shielding the imagined society within its own confines from the harsh and real wilderness which surrounds it. Like Ford’s camera, the sun can look down on it all the same. It’s maybe the most ideal incarnation of this quintessentially Ford observation: that the divide between nature and society is a thin veil. It’s like when Martin breaks up Laurie and Charlie McCorry’s wedding in The Searcher (1956), where their dust-covered brawl in the yard eventually breaks back out inside the Jorgensen house, filling the room with a cloud of red clay and revealing that, at best, the walls simply contain the violence of the outside rather than tame it totally.

For Ford, there’s no tamed wilderness, but one that’s always in the process of being repressed. It’s a part of why Ethan can’t go into the house at the end of The Searchers—he’s an example of the process that must be hidden. Laurie gets to return to the home that’s hers after showing that she’s more “barbaric” than her soon-to-be cousin-in-law whom she went on a racist tirade against not 20 minutes earlier in the film. Laurie’s racism will get to fester, while Ethan’s outright genocidal violence is left behind in the frontier. The new America that’s being built will not be one of perfect harmony, but one where its violence will still exist as the undercurrent of culture, always ebbing and flowing between concealing its machinations and outbursts. This is what makes The Searchers so American and universal (think Jean-Marie Straub’s use of the film to better understand the minds of French settlers in Algeria), but—essentially—Ford’s frontiers aren’t tied to the American West itself.

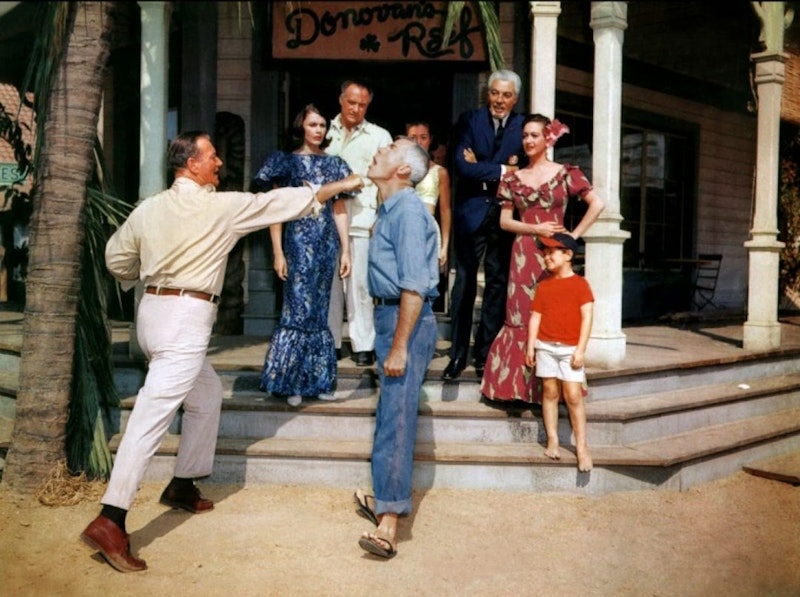

To me, the most beautiful manifestation of Ford’s conception of community is in Donovan’s Reef (1965), wherein a sort of multicultural utopia gathers under the broken church roof in French Polynesia. Colonial bureaucrats, Chinese emigrants, American expats, and Polynesian natives sit together for a Christmas pageant that suddenly gets soaked in a tropical storm. They sing “Silent Night” as the rain beats down on them, a few covered in umbrellas, and some Aussie sailors sitting proudly in the elements. The church roof doesn’t have to be in such disrepair—there’s been many times that alms have been offered for fixing it, with the most recent bout of generosity spent by the attending priest on a new organ instead of finally fixing the roof. It’s ridiculous, and funny, but moreover it’s why Ford thinks this place is so beautiful to begin with: who gives a shit if there’s a roof if everyone’s still willing to gather inside.

Often in Ford’s films the outside will come crashing in, like the wind sweeping Maureen O’Hara into John Wayne’s arms in The Quiet Man (1952), or again in Donovan’s Reef as tropical gusts blast rain into a mansion’s foyer. It’s in part an emotional effect, mirroring the sopping passions of the characters, like a rain-soaked Ava Gardner in Mogambo (1953) looking fiercely at Clark Gable. Again, there’s no true divide between the wilderness and the society hiding within it, and there’s no real divide between the external world and the internal lives of Ford’s characters—when the rain crashes through a door or the wind lifts a veil, it’s as if that force of nature is summoned from within the hearts of the people on screen.

In this way, too, the rain falling through the church in Donovan’s Reef unites the people as much, if not more so, than the song they’re singing or the walls of the building itself. It falls on all of them, and always will, even when the church itself crumbles. The church, they know, is itself a pageant as much as the holiday one they all came for, a little ritual for everyone to gather around. If anything, putting a roof back on the church would only let them fall into the illusion that their world’s built on foundations, not people.